Because I’ve been caring for half a dozen growing chicks—sharing my office with them, transitioning them outside to a coop where two grown chickens live, because I have cleaned up after them and fed them and let them fluff and nest between my inner arm and side body, as if protecting them under my wing, I have been thinking about birds more than usual.

The other day, I sat down on my porch after a stressful battle of protectionism and territorialism had played out between the different ages of chickens in their pen. In the background, I heard wild bird calls and songs. I let the whistles and cackles and trilling press forward in my awareness. The sounds were calming.

My husband has suggested I open the Merlin app on my phone to see the range of birds in our location. He knows how to match bird song to bird name, but it seems like a lot of extra brain work; I prefer to zone out or tune into sensory detail and stop thinking so much when I’m outside. Plus, I’m not really the birding type. And then I catch myself: judging an activity from a place of inexperience. What exactly is the birding type? Why am I behaving in a primal way, like the chickens, pecking at others just because they are not in my immediate flock group?

“Let’s do this,” I motioned to my husband, grabbing my phone and getting in the car to drive to Barn Island, a place where I often see “types” wearing boots and binoculars, straps of gaping-eyed camera lenses crisscrossing their chests, exchanging complicated names of birds and migratory status. And worse, they stand there, for long periods of time, patient and quiet.

We walked the wetlands trail, and my husband comfortably chatted bird trivia with a man whom I would call a birder type. The man said he drove hours for this location because he heard about a sighting of a rare bird (I forget the name). We walked on, and when we looped back, almost an hour later, the birder still lingered at the edge of woodland and wetland, waiting, eager. I felt impatient.

But then I recalled a birding story by Ashley D’Souza. We were in a Grub Street writing group together last year. In “How Birdwatching Helped Me Find My Queer Community—and Myself,” Ashley wrote, “Like the mockingbird, I felt most authentic when I wasn’t boxed into a single mode of expression.” They wrote about how the act of identifying birds one at a time helped with a feeling of being grounded and less alone. This approach appealed to me.

Ashley made friends with others who were also curious about birds, who were willing to care about identities and notice the differences and unique calls around them. When I reread the story, I realized how birding is less about separating and judging and more about connecting and caring.

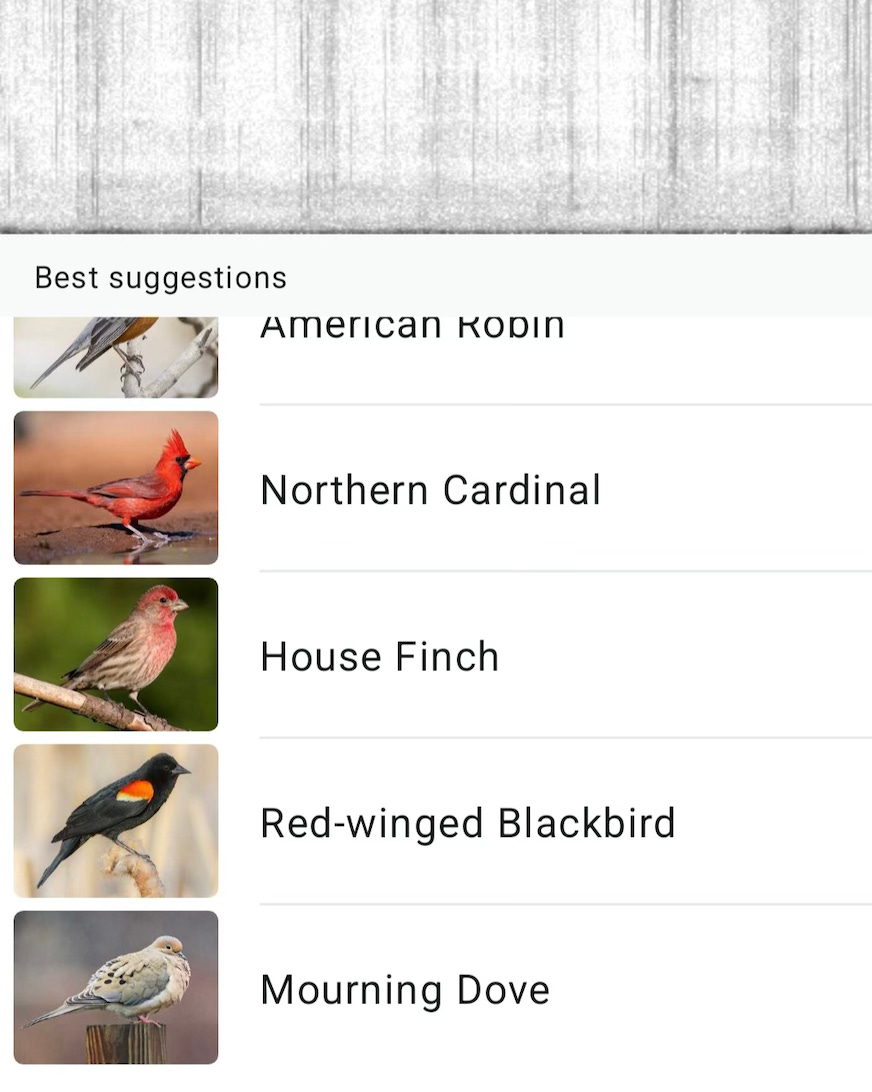

When I was safe in my own backyard, I pulled out the Merlin app and started recording. It was pretty easy to look at my phone’s screen light up with a symphony of bird names based on the sounds it was detecting. I couldn’t believe the abundance. The big players were Song Sparrows and House Sparrows, but there were Tufted Titmouse, Gray Catbird, a Fish Crow and an American Crow, a Common Grackle, a Red-winged Blackbird, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Purple Finch, and then a Spotted Sandpiper. There were 14 birds chattering within five minutes. I couldn’t see any of them. Could there really be a Sandpiper nearby? They are supposed to be on the beach, so it must have been passing by. I was hooked.

I lifted my head and listened, and this time I recognized the Mourning Dove’s crooning, like someone cups their hands on both sides of their mouth to croo-woo a secret code. I recognized the woodpecker rat-a-tat. I didn’t realize that only a few birds are actually songbirds until the app identified Northern Cardinal and American Robin, somewhere above me, singing lyrical whistles and notes like leaders of the band. I became aware of the variety of identities and how beautiful each one’s voice is.

I don’t consider myself a birder or a chicken farmer, just a backyard amateur. But thanks to my husband’s encouragement and Ashley’s story, I’m realizing how important it is to feel comfortable when out in the field, where I am free to observe and be amongst nature. To feel comfortable, it requires caring. To care, I need courage. Identifying one’s nature requires discernment skills, not quick judgment. This hit me: appreciating the common ground and common air where I’m in a symphony, not alone, begins with appreciating each other’s forms of expression, our unique calls in the wild, and listening for the beats of the heart and whir of wings.

Terrific.

Love this, Muireann. And especially the clever title and description of birds in your armpits. So wonderful! Thank you.

Also - I just started watching the residence in Netflix. A who-done-it with lots of birds. If you don’t now it yet - you might love it.